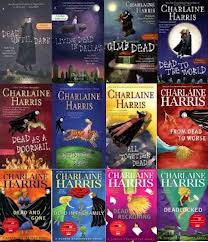

If the perfect beach book (1) offers a likeable heroine (2) tells stories about problems you don’t have, (3) is smart but not taxing, and (4) contains enough sex to make up for the fact you can’t have any since you a sharing a motel room with your kids – then Charlaine Harris’ vampire novels, including the recently published Dead Ever After, are pretty good choices.

If the perfect beach book (1) offers a likeable heroine (2) tells stories about problems you don’t have, (3) is smart but not taxing, and (4) contains enough sex to make up for the fact you can’t have any since you a sharing a motel room with your kids – then Charlaine Harris’ vampire novels, including the recently published Dead Ever After, are pretty good choices.

Certainly, Ms. Harris has earned her success with the character of Sookie Stackhouse, a telepathic barmaid living among vampires, werewolves, witches, fairies, and just-folks humans in the small Northern Louisiana town of Bon Temps.

Much of Sookie’s appeal comes from the fact that she is a normal person. Every day, she gets up and works an unglamorous job. She shops for food, buys gas, cleans her house, and watches TV. At night, she says her prayers. On Sunday mornings, she goes to the local Methodist church. Sookie tries to look after her hard-working but sexually reckless brother. Most of the time, she wonders if she’s done right or not.

Sookie is also appealing because her strength comes from her character, not her paranormal abilities. In almost every fight with a supernatural being – and with many normal humans – Sookie is overmatched, but she will fight all the same if forced, rather than surrender. Sookie also has great courage. She will put herself in danger to help a friend or a person to whom she feels obligated. She will act on principle when it’s against her own self-interest. And she can make hard decisions when her good sense tells her she has to make them.

Another quality of Charlaine Harris’ vampire novels is their social commentary. The books are occupied with how society treats people who are different, and you don’t have to look hard to see the parallels between the vampires in Harris’ novel and homosexuals (and others outside sexual, gender, and lifestyle norms) in our own.

The supernatural can also be seen as the outward manifestation of interior psychology in the novels. Sookie dates vampires and werewolves, which is another way of saying she goes out with no-good men who are blood-suckers and animals, while ignoring the romantic possibilities with her dependable boss Sam, a shape shifter who likes to take the form of a collie.

Sookie’s mind-reading power functions in a similar way. Her telepathy is really the magical extension of her natural intelligence and perceptiveness, qualities that can make a woman living in a small town “different” or “odd” to many of the people around her.

None of these parallels should be taken too far. Harris does not invest every character or story with a deeper meaning. Or put another way, with a nod toward Freud’s famous observation, sometimes a vampire is just a vampire in the Sookie Stackhouse books.

Charlaine Harris is not a great prose stylist, but her writing demonstrates craft, and Harris conveys the sound of Sookie’s voice – and particularly her sense of humor – very effectively.

Her plot architecture is another matter, however. Many of the books are constructed around a series of loosely related incidents, rather than a unified story that has an arc and momentum. The mystery elements of her stories are often thin and feel perfunctory. Her plots seldom twist. And as the series has stretched on, it has become more and more of a soap opera.

This is not such a bad thing for beach books, however, and it means that you can read the series in any order. So try a couple if you discover you just can’t read Woolf’s The Waves while the ocean crashes and the seagulls cry and your neighbors the next umbrella over are blasting Bon Jovi. I couldn’t.