Fans of Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey-Maturin novels value the scenes where Jack and Stephen are playing music in the great cabin of a ship or having particular conversations, like this one which considers the feathers of a paradise bird:

Stephen said, ‘Have you every contemplated upon sex, my dear?’

‘Never,’ Jack said. ‘Sex has never entered my mind, at any time.’

‘The burden of sex, I mean. This bird, for example, is very heavily burdened; almost weighed down. He can scarcely fly or pursue his common daily round with any pleasure to himself, encumbered by a yard of tail and all this top-hamper. All these extravagant plumes have but one function – to induce the hen to yield to his importunities. How the poor cock must glow and burn, if these are, as they must be, an index of his ardour.’

‘That is a solemn thought.’

— H.M.S Surprise, pg.259, Norton paperback edition, 1991

It seems strange, at first, that this should be so. The Aubrey-Maturin novels recount the adventures of Jack Aubrey, a British naval captain, and Stephen Maturin, an Irish-Catalan naval surgeon, naturalist, and intelligence agent, during the Napoleonic wars.

It seems strange, at first, that this should be so. The Aubrey-Maturin novels recount the adventures of Jack Aubrey, a British naval captain, and Stephen Maturin, an Irish-Catalan naval surgeon, naturalist, and intelligence agent, during the Napoleonic wars.

The series is full of battles, storms, shipwrecks, spycraft, political intrigue, the scientific discovery of new species, social manners, and problematic relationships between men and women.

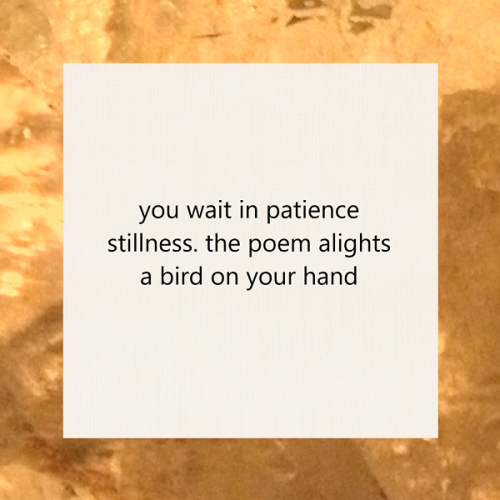

And yet, both O’Brian and his fans always return to the quiet scenes between Jack and Stephen playing music or talking, as they are in the passage above. Why?

The reason has to do, I think, with the consolations literature offers us.

Good books have many uses. They are a pleasure and a comfort. They offer a hedge against loneliness. For centuries, readers have found their own thoughts and feelings in literature, and in finding these have been reassured that they are not alone and unknowable in this world.

And good books console us by offering a permanence to characters we love that we cannot find in the lives of the people we love outside of books.

Not all literature offers this consolation. It is no relief to know that Lear is always at the British camp near Dover, howling with the lifeless Cordelia in his arms, or that Antigone is always hanging in the cell to which Creon condemned her, dead by her own hand. Tragic works of literature offer us many things, but consolation is not one of them.

For consolation, a book must offer us characters who are convincingly human, not simply credible or familiar, and who engage our sympathies through both their virtues and their faults.

The book must also give these characters moments if not of happiness, then of peace and ease, because this is what we wish for ourselves. Among all our troubles and suffering, I think we all want – and believe we deserve – moments of at least modest contentment.

But we cannot stay in these moments or keep the people we love with us in them. Time moves. Circumstance and age separate us, further and further, until death makes the separation final and our only hope becomes reunion in another world; which many of us picture as being much like this one, except that hunger and violence and suffering and disease and death are banished.

Which makes heaven or the Summerlands or the after-life (or even reincarnation in the Indian religions) very much like the passages in the books we love.

Elizabeth Bennet will always be sparkling after dinner in the drawing-room at Netherfield, getting the best of and bettering Mr. Darcy, as alive today as the first moment she was written. Timofrey Pnin will always be playing croquet on the lawn at Al and Susan Cook’s summer house or discovering that Victor’s beautiful glass bowl is not broken after all. Jack Aubrey and Stephen Maturin will always be playing music while the wake of the Surprise stretches away behind them.

In this world, that is consolation indeed. Perhaps not enough. But I’ll take it.