Haiku are the easiest and hardest poems to write in English. Haiku are easy to write because they have a simple format which captures the quality or mood of a moment. They are particularly easy to write if you use lines of variable length rather than follow the 5-7-5 syllable structure which approximates the 17 mora in traditional Japanese haiku.

The same qualities that make haiku easy to write also make them hard to write, however. When it is possible for casual poets to write credible or seemingly credible haiku, then the challenge of writing a haiku that deserves the reader’s attention becomes more difficult.

This challenge has been exponentially increased by the emergence of ChatGPT and other AI platforms. Haiku are well suited to machine creation because of their format and reliance on typical poetic themes and elements. Ask an AI to write a poem and you’ll get doggerel. Ask an AI to write a haiku and you can get something someone might publish. And probably has.

It is within these contexts that I will talk about how to write a haiku. My answers are personal and different from the answers other writers might offer. My goal is not to tell you how you should write a haiku. My goal is to describe how I write these poems with the hope you’ll find something useful to your own work.

The best place to start is with the definition, rules, and format of haiku. I’m not starting with these rules because I think you should follow them. I’m starting with definitions because I think knowing which rules you are breaking – and why you are breaking them – will help make your work better.

What Is a Haiku?

Haiku are short poems that describe nature and imply emotions. That’s a “correct” definition of haiku. It represents many of the poems written in English and it is consistent with definitions offered by other sources.

For example, the Report of the Definitions Committee of the Haiku Society of America states a haiku is “a short poem that uses imagistic language to convey the essence of an experience of nature or the season intuitively linked to the human condition.”

Their definition goes on to discuss useful concepts such as cutting words, the avoidance of metaphors and titles, and other matters. For a rules-based definition of haiku, this report is an excellent source.

The Britannica Online article states a haiku is “an unrhymed poetic form consisting of 17 syllables arranged in three lines of 5, 7, and 5 syllables respectively.”

The article goes on to say, “Originally, the haiku form was restricted in subject matter to an objective description of nature suggestive of one of the seasons, evoking a definite, though unstated, emotional response.”

The Poetry Foundation says a haiku is “a Japanese verse form most often composed, in English versions, of three unrhymed lines of five, seven, and five syllables [which] features an image, or a pair of images, meant to depict the essence of a specific moment in time.”

The Poetry Foundation page discusses how haiku developed in English and their website contains many examples of haiku that break the rules defined by the Haiku Society of America.

I would also read the works of Imagist poets like William Carlos Williams. The Imagists were interested in haiku and I think there is a great deal of similarity between the intentions and effects of their poems and the intentions and effects of haiku. Consider Williams’ famous “The Red Wheelbarrow”.

What Makes a Haiku “Good”?

The first test of a good haiku is that it answers the question “Does it deserve your attention?” with a “yes.” Unless you write a haiku entirely for your own satisfaction, then the poem is seeking attention from readers and its success is measured by how much it earns.

It is also important that the haiku earn attention from the same readers over time. Any haiku might stumble into being read once. These poems are so short that you often read them before you can stop yourself. But when you return to the same haiku again and again, at different times of your life, that’s a sign the poem is good.

Haiku as Meditation

Another test of a good haiku is whether reading it becomes an occasion for contemplation. Poetry has always had a quasi-religious function, which explains why so many poems embrace the ecstasy of the mystic or the didacticism of the Sunday sermon.

In the case of haiku, this function is meditation. Haiku focus on a single moment similar to the way meditation focuses on the present moment. Haiku are often best read in a state of mind where you are open to the thoughts, feelings, and sensations of the poem and accept them without judgment, similar again to the practice of meditation.

Haiku traditionally focus on nature, an all-purpose substitute for God in English-language poetry since the Romantics. Finally, haiku’s use of implied or intuitive meaning – rather than clear statement – make reading them similar to the experience of contemplating a koan in the Buddhist tradition.

All of which explains why Jack Kerouac’s most famous haiku is an excellent example of the form:

The taste

of rain

—Why kneel?

This translation of the famous Basho haiku from an essay in Frogpond is also a good example:

The old pond—

a frog jumps in,

the sound of water.

In the case of the Kerouac poem, the religious context is explicit in the question and implies there is something in the universe worthy of worship and awe. In Basho’s poem, the question is implicit and the haiku takes a neutral position. Perhaps this moment is an intimation of the transcendental meaning of human life or perhaps it is just a random and unremarkable event in our meaningless journey to the void of death.

This is not to say that contemplation is the only experience a haiku can create. You could write a haiku that is purely descriptive or which makes a clear statement or which is humorous or sarcastic. But the traditional form and intentions of these poems make them suitable for reading as meditation, and many of the most successful haiku create a meditative experience.

Aesthetics of Haiku: 5-7-5 Structure, Music, and Design

Another test of a good haiku is whether it has formal or technical or aesthetic beauty. One aspect of this beauty is when the poet successfully solves the difficulty of the form. This is particularly true when the poet follows the 5-7-5 structure but merely writing a brief three line poem can be accomplished enough. Haiku are challenging puzzles and elegant solutions to challenging puzzles have a beauty of their own.

By this standard, the Kerouac haiku is half successful. It is brilliant in its compression. Six words, six syllables. But its form is a bit of a cheat. “The taste of rain. Why kneel?” works just as well but doesn’t signal that this is a poem and the break between the first and second lines is arbitrary. On the other hand, the translator of the Basho poem finds an elegant way to render in English the elegance of the haiku’s Japanese original.

The music of the words is important in haiku as it is with all poems. By this standard, Kerouac gets full points for the beauty of the assonance between the words “taste” and “rain” and “Why” and “kneel” as well as how the soft sounds of the words match the feelings they create.

The Basho translator also does well with the music. The words “old” and “pond” work together. “Frog” and “jump” both have a nice plopping sound and I hear the splash in “water.” The word “in” breaks the music however, and is unnecessary too. You can count on the average reader knowing that frogs jump “in” ponds and make a sound when they do.

Finally, the design of the poem and the look of the words have an effect on its beauty – so much so that I think you lose half the impact of a haiku when you hear it spoken rather than seeing the words. This is different from most other forms of poetry which are as good or better when they are spoken and the appearance of which on the page largely doesn’t matter, especially once the poem runs to any length.

By this standard, both poems are cluttered up with unnecessary punctuation and capitalizations that give visual weight to the least important word. In the case of the capitalization, it’s the “The” which offends. It’s grammatically correct but the effect is to make a functional word stand out more than the words that carry meaning.

In the case of the em dashes (–), I suppose the idea is they are used as a substitute for the cutting words in Japanese haiku. Except in English, the line breaks and the context do that for you. The same is true of the commas and periods when they occur at the end of line. These are grammatically correct but if poets are going to surrender their work to the tyranny of copy editors, all joy has ended. Kerouac’s question mark is useful for clarity however.

Which means if I were to be foolish enough to edit the work of other haiku poets, I would do this:

the taste of rain

why kneel?

the old pond

a frog jumps

the sound of water

The translator of the Basho poem might argue that this edit unbalances the lines and makes the word water stick out and they would be correct. This is an issue I would resolve by centering the lines of the haiku rather than making them left justified.

How to Write Haiku: A Personal View

I follow the 5-7-5 syllable structure and ignore the other rules when I write haiku. I don’t believe the 5-7-5 format is necessary or required. I use it because working within its constraints paradoxically makes it easier for me to write haiku, because the form creates designs that look right, and because it creates poetic experiences that feel right.

I don’t like associating an image from nature with an implied emotion because this often creates stock poems that have been written hundreds of times. There are no more shopworn images in poetry than nature images and they always seem to end up associated with commonplace poetic emotions: ecstasy, despair, longing, wonder, grief, transcendental love, visionary revelations. Include the human body in the universe of nature images and you get the same result.

Because of this, I prefer to write haiku that are descriptive – more like a photograph than a poem – or that make direct statements. I use similes, metaphors, and titles. I’m always looking for non-poetic images and emotions. This can be difficult. Remove the natural world and the strongest emotions from your haiku and you can create a distinctly unpleasant body of work. All the same, I prefer writing this haiku to writing another poem about flowers.

sprawled on the sidewalk

the blue-gloved cop takes her pulse

the city walks on

I don’t think my haiku should be too personal. The purpose of poetry is to give readers experiences they can make their own when they need them. Poets don’t have deeper feelings or better souls than other people. But if we’re lucky, we have a knack for expressing what other people think, feel, and experience but don’t quite know how to say.

So we need to leave room for readers to enter into the experience of the poem and make it their own. The goal should be for readers to say “that’s how I feel” and not “that’s how I feel too.” Which is why I’ve never been happy with this haiku in addition to the fact it ignores the 5-7-5 structure and has familiar images and emotions.

grey clouds

in a blue sky

my mother’s eyes

Finally, writing haiku is about confronting failure and continuing to work. Most artists have to come to terms with the fact that they are not as good as they would like to be. That includes me and many of the haiku on my website are there to remind me how I failed and what not to do the next time.

How to Write Haiku: Personal Examples

That said, I believe I also need to give you examples of haiku I’ve written which I think are good. Among examples of poems that break all the rules except the 5-7-5 syllable format are these:

(cape may)

like scraps of paper

folding themselves into birds

the sea gulls settle

the shimmering light

on the water at sunset

keeps its promises

(broad street)

bright satin, bright brass

the thrilling banjos sing out

as the mummers strut

how soon the joy fades

paper hats and plastic horns

bought on new year’s day

Titles, metaphor, direct statement, the use of haiku as stanzas, no natural images or implied emotions in the case of “(broad street),” and room for readers to decide what the promises might be in the case of “(cape may).” These poems are sufficiently different from standard, rules-based haiku to satisfy me.

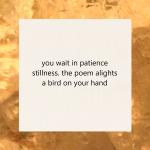

When it comes to poems that make direct statements, I like this one. It has mood and metaphor, it solves the challenge of the form, and it describes my process. Like many writers, I don’t find the subjects of my poems. They find me, and this haiku describes how I create the conditions in which I am found.

This image also shows how I’ve solved a problem with poetry on the internet. In print, you can control where the poem is placed on the page which acts as its frame. On the internet, you can’t. A single haiku can get lost on a web page or among the other elements of a site. This image is a way to solve the problem.

Among my descriptive haiku, I particularly like these two. They have mood rather than emotion. They solve the puzzle of the format. In the case of the “snow” haiku, the poem suggests a story but doesn’t tell you what it is.

I like these among my haiku as meditations. It is especially important to frame these poems so they look right to the reader.

There are more examples of haiku poems in the linked post which I think are good.

How to Write Haiku: In Summary

My personal recommendations are these. Use the 5-7-5 syllable structure to write your haiku. Solving the challenges of the form while paying attention to the look and sound of the poem will yield satisfying results. Look for topics and emotions beyond those expected in haiku. Leave space for readers to enter into the poem and make it their own. Be prepared to fail and follow Samuel Beckett’s advice when you do. “Fail again. Fail better.”