I’ve seen a fair amount of commentary on how eBooks are a threat to the culture of reading (Jonathan Franzen’s reliably cranky remarks at the Hay festival, for example), and I’ve been puzzled by all of it.

I’ve seen a fair amount of commentary on how eBooks are a threat to the culture of reading (Jonathan Franzen’s reliably cranky remarks at the Hay festival, for example), and I’ve been puzzled by all of it.

eBooks may be a threat to traditional business models for publishing and selling books, but I don’t see how eBooks change the essence of reading, and eBooks actually seem to encourage people to read more.

I also think eBooks offer a net benefit to writers and readers, by providing more opportunities for writers, more choices for readers, and the potential for raising royalty payments for writers while lowering the price of books for readers.

All this is not to say eBooks don’t have their problems. But they are interesting new problems, which I think is another point in the eBook’s favor.

Now I have to explain my reasons for all these opinions. Here goes.

The Text is Essential, the Format is Irrelevant

I re-read Henry IV Part 2 recently, going back and forth between an old paperback and my iPad depending on which was more handy, and my experience of the text on each was the same.

I didn’t become a better reader when I was holding the book, or a worse reader when I was holding the iPad. I also didn’t find myself more distractible on the tablet. I looked up maps and historical background on the internet with the iPad, but I consulted the textual notes and essays frequently when I was reading the book.

Further, recent Pew research (“The Rise of E-Reading” published April 2012) find that people who own Kindles and tablets read MORE books than people who don’t own a reading device (24 books a year for e-readers versus 15 books for print readers), and that 88% of e-readers also read print books.

Looking at this data, and considering my own experience, it’s hard to think eBooks have done anything except strengthen book culture.

Now eBooks do change the aesthetics of reading. For people who love books as objects, the beauty of the cover design, the feel of the paper, the weight, a Kindle may not please. If you get satisfaction from looking at your personal library of print books – and I do – your tablet reader will make a poor substitute.

Additionally, the eBook does offer another existential threat to the local independent bookstore, which I care about, as well as the remaining chain retailer, which I don’t. If you want your local store to stick around, go spend your money in it. At the same time, bookstores will also need to work harder to keep their customers coming back.

The Traditional Publishing Model Was Good for Authors and Readers, Too

There were significant advantages to the traditional publishing model. For writers, it mitigated most of the financial risk of publishing. For readers, it offered some assurance of quality.

Both of these advantages grew out of the fact that paper books – especially before computers and the internet – were expensive to typeset, print, ship, distribute, sell, and advertise.

Most writers didn’t have the ready cash to publish their own books, and of those that did, most didn’t have the contacts with buyers and reviewers, much less the money for advertising, that was needed to sell them.

So writers typically surrendered 85 to 90% of the gross revenue from their books to agents, publishers, distributors, and retailers. In return, they risked little of their own money, got access to channels of distribution and promotion, paid someone else to manage the business behind their book, and shared in the profits.

Now companies that published, distributed, and sold books had significant incentives to choose books that would sell and avoid books that wouldn’t, because otherwise they would go out of business.

So all of these businesses became gatekeepers, making judgments on the quality of the books they selected, and only dealing with those they thought would make a profit or which they thought were particularly worthy of finding an audience.

This process gave reviewers and their editors assurance that a new book was worth the time to review; and good reviews gave readers assurance that a new book was worth buying and reading.

This worked for a long time. Everyone knew the deal. Everyone got their cut. Everyone was happy. And then Amazon crashed the party.

Amazon Sells Books: Low Prices Were a Problem; eBooks Are a Mortal Threat

Amazon started as a novelty source of incremental income for publishers. As it grew, it became a direct threat to distributors and bookstores, by making it easier, cheaper, and faster to buy books and music. (Consider the demise of Borders, for example.)

Amazon also squeezed the hell out of publishers margins as it grew, demanding bigger discounts – which are the difference between the list price of a book and the discounted price at which Amazon buys the book – and then selling the books they bought significantly under that list price, which reduced sales in more profitable channels like retail stores.

(How did Amazon do it? Volume, volume, volume! You can make a truck load of money by selling a lot of things for just a little bit more than they cost you.)

Still, no matter how much Amazon squeezed the publishers, it needed them. Someone had to acquire, typeset, design, and print the books. Someone had to advertise the books and make sure they were reviewed. And that someone was publishers because Amazon wasn’t in those businesses.

Until the Kindle.

eReaders like the Kindle, Nook, and tablet computer have all but eliminate the financial risks of publishing books. Writers can publish, distribute, and sell eBooks at virtually no cost directly to their readers, bypassing the traditional model entirely.

Now, the moment when the Stephen Kings and Jonathan Franzens of the world full disengage themselves from the traditional model has not yet come, and there is no absolute guarantee it will.

Only 19% of US adults own an eReader or tablet computer currently, according to Pew. That number needs to be substantially higher before the choice becomes obvious. But the percentage does not have to be anywhere close to 100% before it does.

With eBook royalty rates set at 70% compared to the ten to fifteen percent for print books, the moment when writers will make more money selling fewer eBooks for less money rather than selling more paper books for more money (sorry, you’ll have to read that part twice) will arrive before the eReader is as ubiquitous as television. At which point the eBook model will become self-sustaining.

The eBook Revolution Released a Crap Flood of Biblical Proportions

So, what happens when anyone with two thumbs and a computer can publish an eBook?

Everyone with two thumbs, a computer, and a really great idea for a vampire romance, Zombie apocalypse story, or free-love nudist adaptation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream (that would be me—check out Queen of the Nude) publishes an eBook.

This presents writers and readers with mirror-image problems.

For writers, it is how they make their good book (did I mention Queen of the Nude is a really good book?) stand out from the crap flood. For readers, it is how they pick out the good books from the crap flood.

These problems might make writers and readers think that traditional publishing, with its professional gatekeepers, isn’t such a bad thing after all.

But it is an open question whether the old gatekeepers were actually any better at spotting a book people would like than your average zoo monkey after three martinis. The anecdotal evidence for this success suggests they aren’t, considering how common “X book was rejected 19 times” stories are.

The gatekeepers also overlooked many writers that deserved to be read, and at least on occasion, used their power to promote their friends, relatives, children, lovers, business associates, colleagues, and people to whom they owe money.

With eBooks, every writer has a chance. And with the internet, every eBook has the chance to catch fire and go big. To make that happen, writers are going to have to hustle hard to build an audience and become their own gatekeepers by using blogs, social media, and other channels to provide (hopefully compelling) samples of their work.

Readers have to hustle, too, particularly by writing good reader reviews for each other. The internet often is criticized for releasing a tidal wave of stupidity and it has. But it has also released a tidal wave of intelligence, giving me exposure to smart people who have smart things to say about books I like, which I would have never read any other way.

Readers also have the advantage of eBooks having turned the world into one giant library. Most of the classics are available for free, in versions desperately needing a proofreader I admit. And new books can be sold for as cheaply as $0.99, vastly reducing the risk to readers of trying a new writer or unknown title.

So there’s my take on the eBook revolution. It hasn’t created a perfect world. We could argue whether it has created a better one. But eBooks have created a new world. I’m excited by it.

Read Full Post »

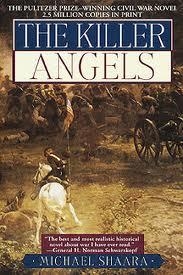

In The Killer Angels, Michael Shaara tells the story of the Battle of Gettysburg during its three most consequential days: July 1 -3, 1863.

In The Killer Angels, Michael Shaara tells the story of the Battle of Gettysburg during its three most consequential days: July 1 -3, 1863.