The purpose of this post isn’t – of course – to convince you these books are bad. Most of them actually aren’t. They just aren’t a good fit for my taste and convictions. Only one book is frankly bad (that would be the Hemingway — sorry Ernest). And the Roth novel is an absolute must-read. Here goes.

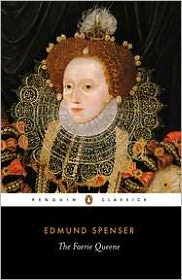

Spenser: The Faerie Queene. An allegorical, epic poem written to compliment Queen Elizabeth the First of England and flatter the aristocracy for their fine taste in the appreciation of “Capital A” art. Spenser’s great technical skill as a poet cannot save a work in which scarcely a single line of genuine inspiration or human feeling can be found.

Spenser: The Faerie Queene. An allegorical, epic poem written to compliment Queen Elizabeth the First of England and flatter the aristocracy for their fine taste in the appreciation of “Capital A” art. Spenser’s great technical skill as a poet cannot save a work in which scarcely a single line of genuine inspiration or human feeling can be found.

Hemingway: The Green Hills of Africa. In this non-fiction account of a month on safari, Hemingway turns himself into a bad imitation of one of his own characters, and his prose follows suit. Painfully mannered and false from beginning to end.

Shakespeare: The Merry Wives of Windsor. The Bard dropped quite a few stinkers on the Elizabethan stage, and it can be hard to pick out the worst. I polled my group of advisors and Wives got the most votes. Coriolanus also made a strong showing, as did Titus Andronicus. (Pericles wasn’t on the ballot because the authorship is disputed.) None of these plays is really so bad that it deserves to be on a most-awful list. It’s their having fallen so far short of their father’s genius children that makes them infamous.

Joyce: Finnegan’s Wake. I may burn in hell for this one, and Finnegan’s Wake may actually be one of the best books every written, but it is just too much damn work. Finnegan’s Wake is like one of those monasteries at the top of a mountain, where after decades of constant study, hard work, self-denial, meditation, and no sex at all, you achieve total consciousness. Total consciousness sounds great, but I have kids to take to the park, and my wife is expecting me to cook dinner tonight, and I just don’t have the time. And, let’s be honest, I’m not smart enough to read this book, either.

Dante: Paradiso. Okay, I’m definitely going to burn in hell for this one, but that’s the problem. Hell is more fun. Inferno was a rockin’ good time. Purgatorio was pretty good, better in the beginning, then it got slow. But there’s simply no fun in heaven. What there is, instead, is Thomas Aquinas nattering on about Francis of Assisi and Peter Damian (I don’t even know who that is) chatting up Dante about predestination. And if you don’t read Italian, and I don’t, then you have to deal with the English translations, which do to Dante’s poetry what a cheap plastic transistor radio – that kind you could buy in 1973, with the little black wrist strap – does to Beethoven’s 9th symphony.

Stendhal: The Charterhouse of Parma. A thoroughly mediocre novel that engages the reader’s imagination on exactly one point: Why is this book considered a classic?

Lewis: Babbitt. A satire is supposed to make the targets of its ridicule look ridiculous, but Lewis’ satire is furious and implacable and, finally, a cheat. Lewis portrays George Babbitt as so vulgar and foolish that it’s impossible not to feel superior to him, which is the cheapest flattery a writer can offer a reader.

Lewis: Babbitt. A satire is supposed to make the targets of its ridicule look ridiculous, but Lewis’ satire is furious and implacable and, finally, a cheat. Lewis portrays George Babbitt as so vulgar and foolish that it’s impossible not to feel superior to him, which is the cheapest flattery a writer can offer a reader.

Roth: The Breast. Roth’s parody of Kafka’s Metamorphosis tells the story of a man who wakes up one day to discover that he’s turned into a giant breast. I’m not making this up! Perhaps no major writer has set out to intentionally write a bad book and succeeded so spectacularly. Transcendentally, fabulously awful!