I am thinking of aurochs and angels, the secret of durable pigments, prophetic sonnets, the refuge of art. And this is the only immortality you and I may share, my Lolita.

Nabokov’s masterpiece is frightening story of abuse, a Gogolish road-trip through post-war America, a funhouse of unreliable mirrors, and a tale of selfish vice vanquished (but not excused) by love. After Humbert Humbert destroys his doppelgänger in the fairy-tale mansion on Grimm Road, he and Nabokov make a furious last dash to preserve Dolores Haze from time and death. They succeed.

Archive for the ‘Literature’ Category

Quote & Comment | from “Lolita” by Vladimir Nabokov

Posted in Literature, Vladimir Nabokov, tagged Literature, Vladimir Nabokov on October 23, 2012| 5 Comments »

“Madame Bovary” by Gustave Flaubert | 100 Word Reviews

Posted in Literature, tagged Literature on October 4, 2012| 10 Comments »

Emma Bovary should have stayed on the farm.

Emma Bovary should have stayed on the farm.

Instead, she marries an oafish health officer and rises into the middle class of a country town, where she finds boredom, loneliness, empty promises from romance novels and religion, and fury at the cages in which 19th-century France placed women.

Flaubert’s universe is barren of virtue. There is no tenderness or compassion, no understanding or true friendship, no curiosity or wonder in Madame Bovary. No love either, despite all the talking of it.

Everyone is crass and venal, foolish, pompous, scheming and self-serving, craven, dastardly. Words fail the characters – even Flaubert’s words. The novel’s people are surrounded by his exquisite descriptions of wedding revelry, bustling towns, the beauty of nature, but Flaubert’s words make no impression and bring no consolation.

All anyone sees in Emma Bovary is her beauty, her clothes, and her body. So perhaps it makes sense that when Emma tries to solve the problem of her life – a problem she feels but can’t articulate – she turns to sex and shopping. They lead her to misery and destruction, of course.

I don’t think Emma could see other choices. Who is at fault? Emma Bovary herself? The society in which she lived? Or the world Flaubert made for her? Probably all three.

Acute Stress Disorder in Beatrix Potter’s Peter Rabbit

Posted in Fiction, Literature, tagged Fiction, Literature on September 30, 2012| 89 Comments »

Before Beatrix Potter became the author of children’s books such as The Tale of Peter Rabbit (1902), she was a gifted natural historian and scientist.

Before Beatrix Potter became the author of children’s books such as The Tale of Peter Rabbit (1902), she was a gifted natural historian and scientist.

So it’s not a surprise that Ms. Potter’s illustrations closely resemble the animals on which her characters are based or that she writes unsentimental stories that display a strong understanding of human (rather than animal) psychology.

This is certainly the case with Beatrix Potter’s most famous character, Peter Rabbit, whose trauma in Mr. McGregor’s garden is so realistically portrayed that cheeky amateurs with access to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM IV) could diagnose him with Acute Stress Disorder if they liked.

In The Tale of Peter Rabbit, Peter’s mother tells him not to go into Mr. McGregor’s garden because “your father had an accident there; he was put in a pie by Mrs. McGregor.”

This does not deter Peter, who runs straight to the garden and encounters Mr. McGregor. In the subsequent chase, Peter loses his shoes and coat and catches cold while hiding in a watering can. Peter escapes and his mother puts him to bed with a dose of camomile tea.

Trauma is a cause of Acute Stress Disorder, and I think this experience qualifies as a traumatic event according to the DSM-IV because Peter was both “confronted with an event that involved actual or threatened death” and responded with “intense fear [and] helplessness.”

We see the symptoms of Acute Stress Disorder in The Tale of Benjamin Bunny, which picks up Peter’s story the next day.

As the book opens, Peter’s cousin Benjamin finds him “sitting by himself” looking “poorly” and “dressed in a red cotton pocket-handkerchief.”

Benjamin leads his cousin away toward the McGregor’s garden without either agreement or resistance from Peter.

From this description, we can find in Peter (1) an absence of emotional responsiveness and a reduction in awareness of surroundings and (2) anhedonia or lack of interest in activities that used to bring enjoyment, both of which are characteristic of Acute Stress Disorder.

Once in the garden, Peter Rabbit displays three more important symptoms: (3) poor concentration, (4) marked symptoms of anxiety, and (5) increased arousal, hypervigilence, and an exaggerated startle response.

Once in the garden, Peter Rabbit displays three more important symptoms: (3) poor concentration, (4) marked symptoms of anxiety, and (5) increased arousal, hypervigilence, and an exaggerated startle response.

There are three instances of poor concentration in the tale. First, Peter falls “down head first” from the pear tree he and Benjamin are using to enter the garden. Peter and Benjamin pick onions as a present for Peter’s mother, but Peter drops half the onions at one point in the tale and drops the others a little later.

Peter is also clearly anxious and hypervigilent during his return visit to Mr. McGregor’s garden. While Benjamin is collecting the onions, Ms. Potter notes “Peter did not seem to be enjoying himself; he kept hearing noises.”

Peter also doesn’t join Benjamin in eating Mr. McGregor’s lettuces either, instead saying that “he should like to go home.” When the two rabbits walk among Mr. McGregor’s flowerpots, frames, and tubs, “Peter heard noises worse than ever, his eyes were as big as lolly-pops!”

It is in this emotional state that Peter and Benjamin are trapped under a basket by one of the McGregor’s cats for five hours. Ms. Potter writes it was “quite dark” and the “smell of onions was fearful” under the basket. Both Peter Rabbit and Benjamin Bunny cry.

The little rabbits are saved by Benjamin’s father, old Mr. Benjamin Bunny, who cuffs and kicks the cat into the greenhouse, then whips both Benjamin and Peter with a switch.

Peter returns home, where his mother forgives him because she “was so glad to see he had found his shoes and coat” and all seems to end well. The last drawing in the story shows Peter folding up the pocket-handkerchief with the help of one of his sisters.

But Peter’s trauma isn’t resolved as much as it is ignored, and the ambiguity of this resolution hangs over the end of the story. I suspect that the effects of Peter’s untreated trauma will linger for years, making it hard for Peter to find stable employment as an adult and perhaps leading to the self-medicating abuse of rabbit tobacco.

Peter Rabbit isn’t the only psychologically realistic character who experiences trauma in Beatrix Potter’s stories. Mr. Jeremy Fisher is nearly eaten by a trout and resolves never to go fishing again. Jemima Puddle-Duck’s eggs are saved from a fox by the collie dog Kep, only to be gobbled up by puppies before Kep can stop them.

Even Mrs. Tittlemouse, who is threatened by no more than a series of unwanted visitors in her sandy house, lives under the constraints imposed by her obsession with cleanliness and order.

Beatrix Potter’s dispassionate examination of life’s menace has earn her books readers for more than one hundred years. I have to ask, however: “Why do we let children read them?”

“The Wings of the Dove” by Henry James | 100 Word Reviews

Posted in Literature, tagged Literature on August 13, 2012| 6 Comments »

I had a long slow argument with Henry James while reading The Wings of the Dove. Was he an immortal genius? Or a purveyor of pretentious soap operas? Here’s who won the argument:

I had a long slow argument with Henry James while reading The Wings of the Dove. Was he an immortal genius? Or a purveyor of pretentious soap operas? Here’s who won the argument:

“On that especial issue, Peter made something like a near approach, taking into account his great reasons, the particulars and nuances and complexities, they being, of course, more important than the main point, they being really fine, and grand, and ravishing, and although he hung fire on his answer, and really, who might blame him, before committing himself, as it were, to a more definite position, which if stated plainly, might fall a little flat, might seem a little thin, might reveal too baldly a poverty of thought and a desolation of feeling, conveniently concealed in a thicket of syntax, great flashes of brilliance aside, yet he did half commit himself, in the end, all of which is to say, perhaps, he wouldn’t decide James wasn’t coming out something more ahead than not.”

Re-reading “Steppenwolf” by Hermann Hesse in Middle Age

Posted in Literature, tagged Literature on July 31, 2012| 4 Comments »

Hermann Hesse, author of books such as Siddhartha and winner of the 1946 Nobel Prize in Literature, is the perfect writer for teenagers. His novels are painfully earnest, full of sensitive characters who are struggling against the soul-destroying conventions of society and searching for transcendence.

Hermann Hesse, author of books such as Siddhartha and winner of the 1946 Nobel Prize in Literature, is the perfect writer for teenagers. His novels are painfully earnest, full of sensitive characters who are struggling against the soul-destroying conventions of society and searching for transcendence.

This description certainly fits Harry Haller, the central character in Hesse’ most famous book, Steppenwolf. And it’s not hard to see why Harry would appeal to adolescent readers (despite the fact he’s nearly 50 years old). Harry is grumpy, gloomy, brilliant, artistic, misunderstood, rejected, spends a lot of time alone in his room brooding, and is – turns out – pretty horny. This exactly describes the kind of teenager who would bother picking up Steppenwolf in the first place.

The question is, for those of us who read Steppenwolf twenty or thirty years ago, Should we bother reading it again?

The answer is “sorta”.

Steppenwolf is still utterly humorless and Harry is still gloomy, misunderstood, brooding. What stands out now is how dull Harry Haller is. Hesse keeps telling us how fine a soul Harry has: how intelligent is he, how artistically refined, and how much he suffers.

But the only evidence we have of Harry’s genius is Hesse’ say-so. Nothing in Steppenwolf persuades us that Harry is as remarkable as Hesse claims, and without any tangible signs of brilliance, Harry is rather uninteresting, except for when he’s being petulant.

Steppenwolf also displays that vanity particular to the aging male animal, which is the magical belief that beautiful young women find us attractive.

In the real world, young women don’t fall for decaying misanthropes unless they have a sum of money and Harry doesn’t. But Hesse asserts that not one, but two gorgeous young girls are fascinated by Harry and that he is still capable of prodigious feats of physical love with them.

What saves Steppenwolf is how thoroughly Hesse destroys any sense of value we might have for Harry’s genius. Hesse still sees Harry as a unique soul – but a unique soul leading a useless existence. Harry is a man who has forgotten how to laugh or find pleasure in life. He’s a fool who should be pitied, and scolded, and taken by the hand and pulled away from his stubborn loneliness and self-importance.

When this happens, Harry does become interesting. He begins to feel human. He engages our sympathy. And he makes the long hallucinatory sequence that forms the middle-end of Steppenwolf credible rather than ridiculous because Harry feels like a convincing person in it.

Finally, the last pages of the book work for readers of a certain age. Steppenwolf closes not with Harry triumphing over his old self, but rather with him discovering that he is the same person he always was despite his best efforts.

I suspect the young don’t much like this ending. The young believe they can be anybody they want to be (and they should believe this).

Unfortunately, for those of us who have been living with our adult selves for a couple decades, the ending of Hermann Hesse’ Steppenwolf bears an unhappy resemblance to the truth.

“As You Like It” by William Shakespeare | 100 Word Reviews

Posted in Literature, William Shakespeare, tagged Literature, William Shakespeare on July 24, 2012| 5 Comments »

In As You Like It, Shakespeare banishes all unhappiness, unless it springs from love.

In As You Like It, Shakespeare banishes all unhappiness, unless it springs from love.

The play follows a multitude of characters driven from a nobleman’s court to exile in the Forest of Arden, where they find refuge from the ambition, intrigue, envy, and striving of the world.

There a usurped Duke philosophizes on his new freedom; a lord tends his melancholy like a garden; and the clown Touchstone pursues his fooling to the edge of the sublime – but the show belongs to the misery and ecstasy of love and to the superlative Rosalind, mistress of all situations and persons except her own wild heart.

There are familiar Shakespearian tropes in As You Like It. The instantaneous and absolute way love conquers. The woman dressed as a man who hides from her love and is loved by the wrong person in turn. And the character who arranges events to create maximum drama, even as the audience is left wondering what motivates her manipulations.

No matter. The dialogue is superb. Rosalind bewitches men and women, on and off stage, in equal measure. And all ends happy in this most delicate of Shakespeare’s comedies.

“Dead Souls” by Nikolai Gogol | 100 Word Reviews

Posted in Literature, Vladimir Nabokov, tagged Literature on July 6, 2012| Leave a Comment »

Nikolai Gogol’s Dead Souls first gained fame as a caustic satire of Russian society when it was published in 1842. Today’s readers will value it as a mesmerizing phantasmagoria of human vice, mendacity, and mediocrity.

Nikolai Gogol’s Dead Souls first gained fame as a caustic satire of Russian society when it was published in 1842. Today’s readers will value it as a mesmerizing phantasmagoria of human vice, mendacity, and mediocrity.

The title refers to a defect in Russian law that frequently required the owners of serfs (or “souls”) to pay taxes on their human property even after the serfs have died. The story follows Chichikov, a small-time confidence man, as he buys these souls at steep discounts, saving the owners from the taxes and gaining for himself fraudulent collateral he can use in subsequent schemes.

Gogol offers a parade of vividly detailed human caricatures described in language which is baroque, grotesque, exuberant, and exact. Fans of Vladimir Nabokov will find much that is familiar in Gogol’s prose. I enjoyed the translation of Dead Souls by Bernard Guilbert Guerney which Nabokov recommended .

“To the Lighthouse” by Virginia Woolf | 100 Word Reviews

Posted in Literature, tagged Fiction, Literature on June 27, 2012| 4 Comments »

Modernists can have a high strike-out to home-run ratio – but Woolf knocks it clean out of the park with To the Lighthouse.

Modernists can have a high strike-out to home-run ratio – but Woolf knocks it clean out of the park with To the Lighthouse.

The novel is organized into three sections. The first and third describe two vacations, separated by ten years, the Ramsay family takes to their house in the Hebrides. The second describes that house during their ten-year absence, slowly decaying under the influence of weather and time, while out in the world, members of the Ramsay family die.

To the Lighthouse is conflict rich but plot poor. Woolf gives us vivid, fragmented portraits of her characters during two brief moments in their lives, then asks us to assemble the pieces to understand who they were, what they’ve become, and what has changed them.

Her writing throughout the novel is masterful — Virginia Woolf does with words what Vermeer does with paint — but the second section is simply astounding. There is no way the description of an empty house should be moving. And yet often enough I read it through tears.

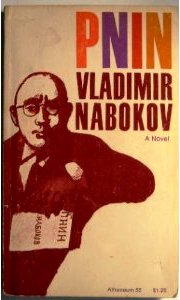

“Pnin” by Vladimir Nabokov | 100 Word Reviews

Posted in Literature, Vladimir Nabokov, tagged Literature, Vladimir Nabokov on June 13, 2012| Leave a Comment »

The one true moral responsibility of literature is to strengthen our imaginative sympathy for other people. Nabokov’s exploration of the deep humanity within the seemingly comic figure of Professor Timofrey Pnin is the most perfect example in English. The story is episodic, but the writing is flawless.

The one true moral responsibility of literature is to strengthen our imaginative sympathy for other people. Nabokov’s exploration of the deep humanity within the seemingly comic figure of Professor Timofrey Pnin is the most perfect example in English. The story is episodic, but the writing is flawless.

Nabokov’s books are full of arrogant misanthropes. So look here for Victor’s glass bowl and “the shining road” on which Pnin escapes into Pale Fire, where Nabokov makes him the head of a thriving Russian department.

“Emma” by Jane Austen | Review of the Novel

Posted in Literature, tagged Literature on May 30, 2012| 11 Comments »

I may just be a middle-aged Jane Austen fanboy – but Austen keeps earning my admiration novel after novel, and she’s done it again with Emma.

I may just be a middle-aged Jane Austen fanboy – but Austen keeps earning my admiration novel after novel, and she’s done it again with Emma.

Since chances are good you already know the book, I’m going to skip the review and serve up random observations. I reveal much of the plot and all of the surprises in Emma, however. So, spoiler alert. Here goes:

Emma is a Comedy

The proper response to this observation is – I realize – “Duh”. But it’s also a remarkable fact because Austen’s other books are romantic dramas (except for Northanger Abbey, which is a parody of Gothic novels).

One of the qualities I admire in Austen is that she rarely writes the same book twice, even though her novels share so many themes and situations.

For example, Elizabeth Bennet and Fanny Price are about as different as two characters can be, and their novels are very different in tone, pacing, and plot. But Pride and Prejudice and Mansfield Park are both major achievements.

In Emma, Austen gives us a third variation which I think is easily the equal of these novels – and it’s a comedy. How many writers succeed in more than one style?

Emma is a Comedy … with a Conscience

Really, this is just ridiculously difficult to pull off and Austen makes it look easy.

The problem with comedy is that it is almost always based on pain. But you can’t laugh at a character and empathize with her at the same time.

To deal with this problem, writers usually locate their stories in a “comic” world that is largely free of consequences and death OR they reduce, deny, ignore or attack the humanity of their characters.

Austen does neither. Emma Woodhouse is a comic figure, and some of her foolish mistakes are funny, but it is Emma’s good intentions and the deep shame, regret, embarrassment, and pain she feels at her mistakes that make her more than a figure of fun.

And Emma is not alone, of course. Miss Bates is even more of a comic figure. In fact, there may be no greater clown anywhere in Austen’s work, and yet Miss Bates is treated with respect. When Emma insults Miss Bates during the excursion to Box Hill, Mr. Knightley rides to Miss Bates’ defense (“It was badly done indeed!”) and Emma weeps almost all the way home.

This is not comedy that produces belly laughs. It is delicate comedy, designed to make you smile, and possessing a grace and lightness that in its total effect is indistinguishable from wisdom.

Indeed, could we say the definition of wisdom is moral seriousness combined with laughter?

Emma’s only equal in this category I know is Shakespeare’s As You Like It. That’s pretty good company.

Everyone is Mistaken about Love

What a brilliant, delightful, simple conceit around which to construct a novel. Everyone is wrong about everyone else’s feelings, basically all the time. And yet it turns out happy.

Here’s a list of mistakes about love in Emma:

• Emma thinks Mr. Elton loves Harriet Smith

• Mr. Elton thinks Emma loves him

• Emma thinks Mr. Dixon loves Jane Fairfax

• Mrs. Weston thinks Mr. Knightley loves Jane Fairfax

• Emma thinks Frank Churchill loves her

• Mr. Weston, Mrs. Weston, and Mr. Knightley think Emma loves Frank Churchill

• Emma thinks Mr. Knightley loves Harriet Smith

This list doesn’t include Emma’s serial mistakes with Harriet Smith, which are persuading Harriet to fall out of love with Robert Martin; persuading Harriet to fall in love with Mr. Elton; and persuading Harriet to fall in love with Mr. Knightley while thinking she was persuading Harriet to fall in love with Frank Churchill.

It also doesn’t include the biggest mistake of all: no one realizes that Frank Churchill and Jane Fairfax are in love.

Emma is the Snob on Top

As I said, I admire Austen for rarely writing the same book twice. Emma is unique in Austen’s work as a comedy. It’s also unique because its major characters sit on top of the novel’s social order.

In Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, Mansfield Park, and Persuasion, the main characters are all marginalized or dispossessed in their societies or families, and generally opposed by those who rank higher or think more highly of themselves.

In the novel, Emma Woodhouse and Mr. Knightley are the rulers of their set. Emma is aware of her social position, guards it carefully, and is jealous when it is infringed. (For example, part of the offense Emma takes at Mr. Elton’s marriage proposal is his presumption that he was Emma’s social equal … an heiress of 30,000 pounds!)

Mr. Knightley is less particular than Emma about the niceties of his status, but he wields his power with the same sense of entitlement. Mr. Knightley has perfect confidence in his judgment of every situation, and rarely yields to the opinions of other people. He does not give offense wantonly, but he doesn’t worry about offending Mrs. Elton when she presumes to guide his choices or the Westons when he speaks poorly of Frank Churchill.

This is significant because Emma and Knightley would be the villains in other Austen novels. By all rights, Harriet Smith and Robert Martin should resent Emma’s interference in their lives, the way Elizabeth Bennet resents Lady Catherine’s in hers.

But Harriet is very sweet, and not all that bright, and she seems to feel Emma’s hugely mistaken good intentions more than she notices Emma’s mistakes. As for Robert Martin, we don’t know. In the end, he got the woman he loved, and as practical man of good sense, apparently content with his station, perhaps he decided the rest didn’t matter.

From drama to comedy, and from villain to hero, these are two reasons to admire Emma. And now I think I’m done with Jane Austen for a time. On to the next author!